Fire Island Fashion History- Antonio Lopez

Antonio Lopez, Fire Island Pines, c. 1978

1943-1987

As the 1970’s arrived the Pines became the IT destination for many in the Fashion world. Some for the backdrop it provided, and many for the privacy and fun. Fashion Illustrator Antonio Lopez was one. Hanging out with friends french sylist/photographer Jean Eudes Canival at his, and Fashion designer partner Fred Lansac’s home. Pool guests included actors David Duchovny and Jason Beghe.

All photographs are courtesy The Estate and Archive of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos. More information can be found at www.theantonioarchives.com or on social at @the_antonio_Archives

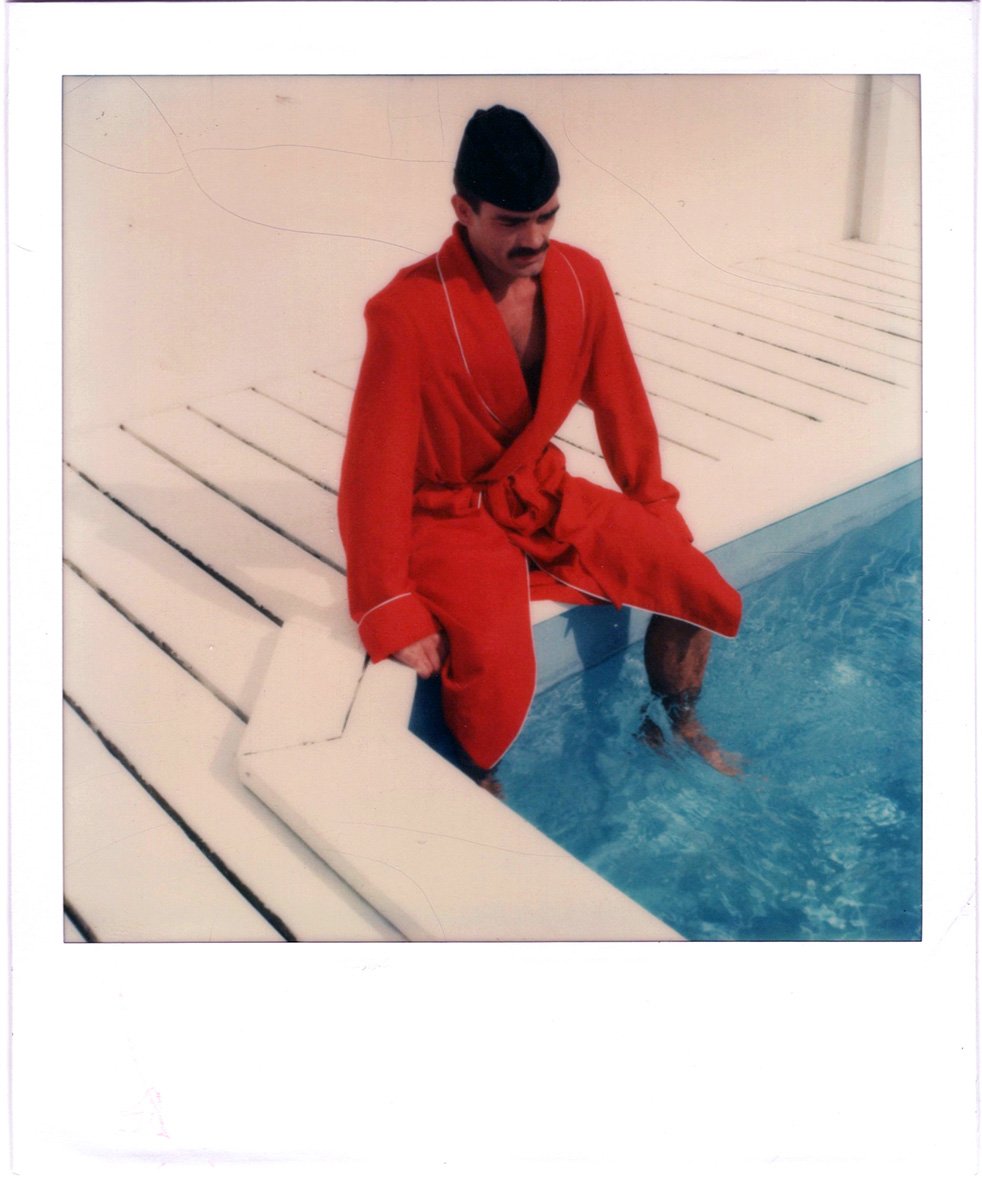

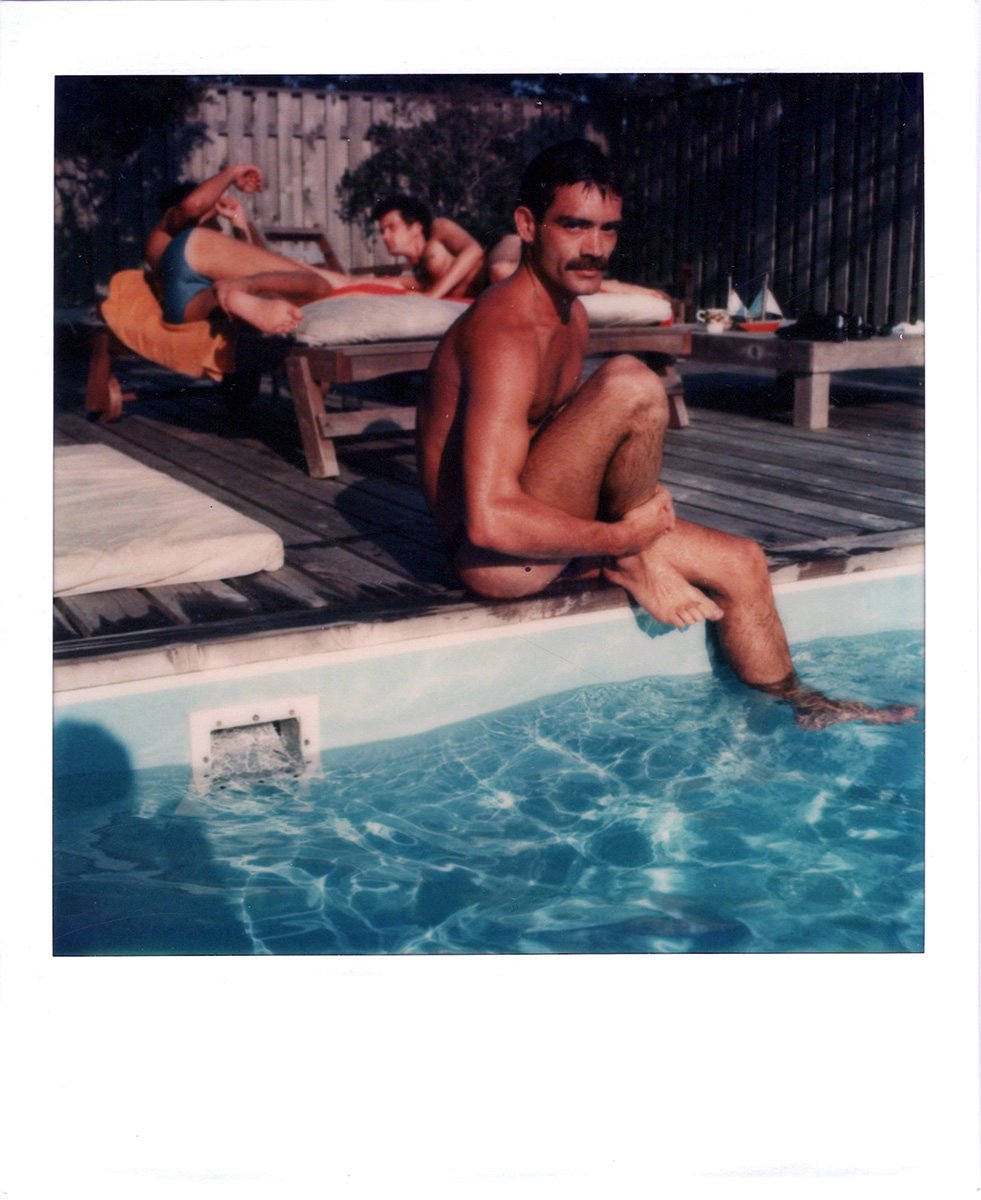

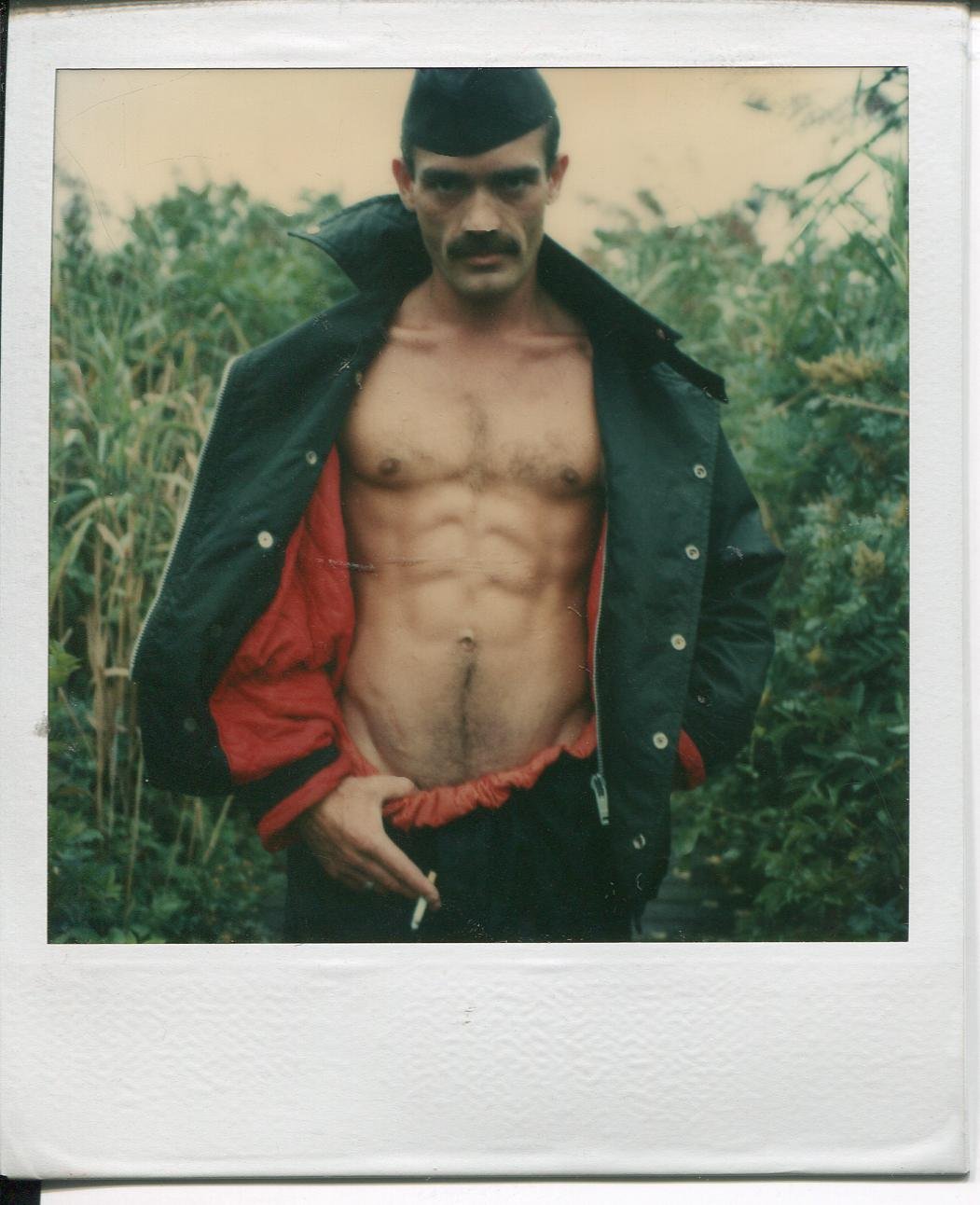

Jean Eudes Canival (below) was quite the character enjoying the freedom of Fire Island completely…

Jean Eudes Canival, Fire Island Pines, August 1979. Kodak Instamatics. © The Estate of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos

Jean Eudes Canival, Fire Island Pines, August 1979. Kodak Instamatics. © The Estate of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos

Antonio and longtime partner Chris Poracchia would visit often where there always fun to be had.

Chris Poracchia and Antonio Lopez, Fire Island Pines, 1978

Chris Poracchia and Antonio Lopez, Fire Island Pines, 1978

Chris Poracchia and Antonio Lopez, Fire Island Pines, 1978

Bob Starr, Don Hall, Heloise, Chris Poracchia, and Antonio Lopez, Fire Island Pines, 1978

Antonio, Chris Porrachia, Matthew Olzsak Fire Island Pines, 1978

Born in Utuado, Puerto Rico, in 1943, Lopez moved with his family to Spanish Harlem when he was 7 or 8 years old. His father found work as a mannequin maker and his mother as a seamstress. Lopez had always sketched designs for his mother, but he formalized the interest as a preteen at New York’s Traphagen School of Fashion, then at the High School of Art and Design, and finally at the Fashion Institute of Technology. There, he met Juan Ramos, a fellow Puerto Rican transplant. The two would become partners in the creative (and, for a few years, romantic) sense, with Ramos doing everything from researching inspiration to coloring in Lopez’s outlines. (It’s generally understood that the signature “Antonio,” when it appeared on a magazine page or in commercial work, stood for the work of both men.)

In 1962, while still a student at FIT, Lopez began working for Women’s Wear Daily as an illustrator. (Before the widespread adoption of photography in fashion magazines, sketch artists were the ones responsible for conveying the latest trends to readers.) He dropped out to do the job full-time, and he did it well, landing bigger assignments and, in short order, covers. But the job wasn’t enough. When Carrie Donovan at The New York Times reached out with freelance work less than a year into the gig, he took the leap. WWD owner John Fairchild summarily fired him, but by then Lopez had made a big enough name for himself that it didn’t matter.

Lopez’s work before that had been more traditional, full of long, thin-limbed figures that wouldn’t be out of place in a designer’s sketchbook. That was the expectation for fashion illustration at the time, or at least what was left of it as photos took over magazine real estate. But in a 1963 assignment for the Times, Lopez drew thicker figures that paid homage to the Cubist painter Fernand Léger, demonstrating a willingness to push the form in new directions. “When I came into fashion illustration, it was a dead art, real boring, catalogy, very WASPy,” he told People in 1982. “I gave it a transfusion.” Soon he was pumping out motorcycling blondes for British Vogue and lazy, lingerie-clad ingenues for McCall’s. When psychedelics infused popular culture, his work took on their warbly sherbet aesthetic.

Though they were already fashion-world famous before they arrived in France, things took off even further once they got there. Lopez’s entourage, which rivaled Andy Warhol’s Factory crew as a New York nightlife mainstay, included Ramos and the makeup artist Corey Tippin, as well as the models Donna Jordan, Jane Forth, and Pat Cleveland. The women became Antonio’s Girls, as the clique became known. Not only was it a multiracial coalition— Cleveland was a rare black supermodel, and Grace Jones and Tina Chow would eventually join in—but they performed the model role in fresh, new ways. They painted their faces in wild colors, at Lopez’s suggestion, and they refused to walk staidly down the runway; they danced, they smiled, they had fun. (Cleveland was known to occasionally strip mid-party— or mid-catwalk.) They were Antonio drawings come to life, essentially.

Lopez did not live a long life, just 44 years. He died in 1987 of complications from AIDS. But in those four decades he unleashed a tidal wave of creativity. In 1978, he supplied a diary page for GQ. It featured slinky male figures, their hips cocked and muscles prominent, a phalanx of his Girls, and some of his famous friends—Grace Jones, Jessica Lange, Jean-Paul Goude. Lopez had been back in the U.S. for a couple years, and the intro text read, “New York City is still America’s melting pot. For Antonio Lopez, nothing generates the city’s electricity more than the diverse people who are drawn to it.” It could be said that Lopez generated plenty of that electricity himself. BY MELVIN BACKMAN GQ Magazine October 22, 2019