Ship N Shore Est. 1953/ Pines Pantry 1974

The First and Only Grocery Store in Fire Island Pines

By Juan A. Ramirez NY Times July 22,2022

For nearly 70 years, Pines Pantry has been a one-stop shop for fresh fish, baked goods and lube.

WHEN IT OPENED in July 1953, the Ship’N Shore became the first general store in Fire Island Pines, a square mile of land that sits opposite Sayville, Long Island, about 50 miles east of downtown Manhattan. Originally owned by Warren Christopher and Billy Stryker. At the time, the area was sold as the perfect family summer getaway, a spot for parents and children alike.

Landowners The Home Guardian Company of New York encouraged building fast as to help sell the new community called Fire Island Pines.

Almost 70 years on,

the Ship’N Shore looks quite different, as do the people who shop there. Today’s customer is more likely to be dressed in a Speedo and a leather harness than they are to be pushing a stroller.

That’s because the Pines, as it’s often called, has become an almost mythical destination for gay men from around the world, a near-halcyon oceanfront oasis where uninhibited intimacy among men isn’t just easy, but encouraged.

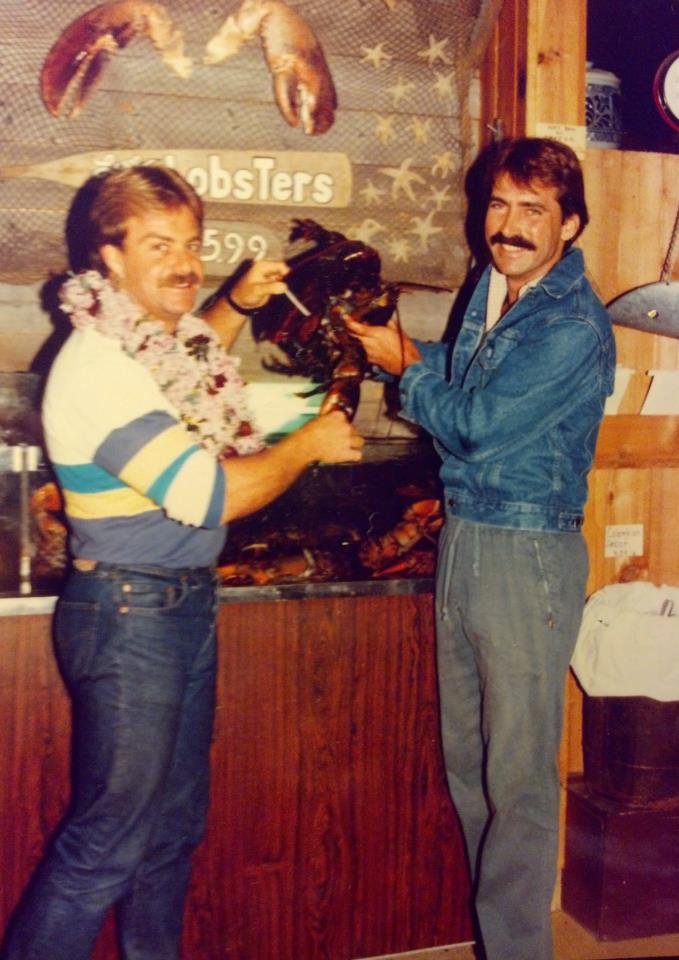

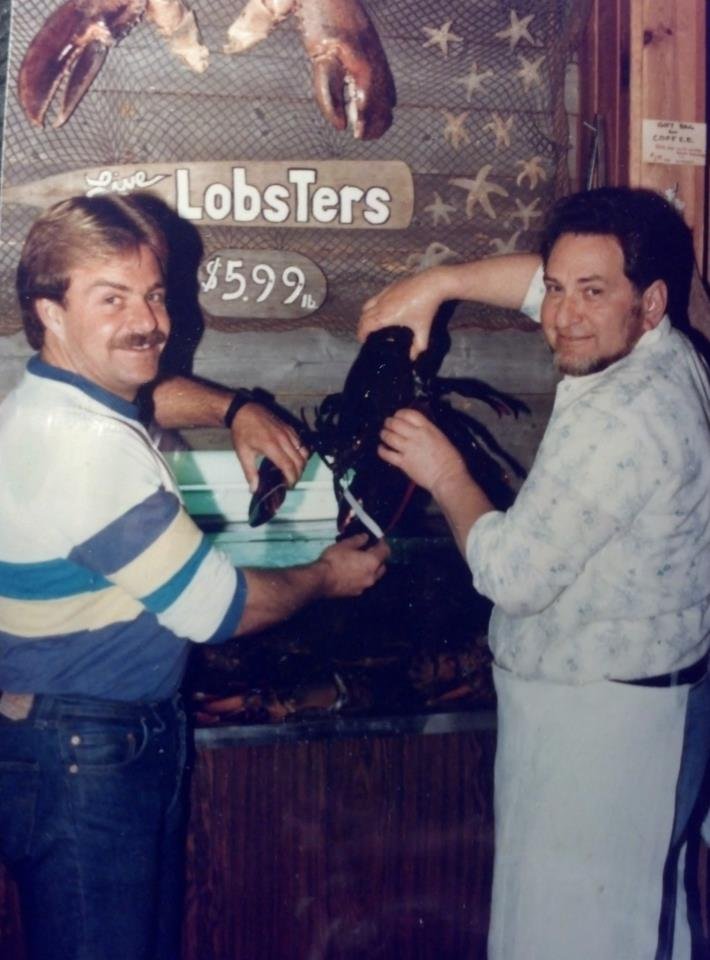

Around 1974, a few years after the Stonewall riots catalyzed the queer liberation movement, word began to spread about a place not so very far from New York City where gay men, who were usually forced to be discreet, could enjoy themselves with markedly less public scrutiny. The Broadway producer Myron Tucker, then 27, and his boyfriend, Jack Rohlfing, used the profits and experience they’d gained running a candy store in the Pines to buy and revamp the Ship’N Shore, which was lagging behind its increasingly sophisticated clientele, and renamed it Pines Pantry. It is now the only place in the area that offers fresh produce, breakfast sandwiches and lube.

In the late 1970s, Tucker and Rohlfing hired Eric Schrader and Laurie Schuhmann, a pair of teens from the quiet town of Sayville, to work summers as the Pantry’s back- and front-end managers. “They were like our second parents,” says Laurie of the couple. “They molded us into the people we are today.” A few years into their jobs there, the first cases of AIDS were discovered in New York. The number of visiting gay revelers plummeted, and the straight crowd that used to ferry over for sunset cocktails all but disappeared. When Tucker and Rohlfing learned they, too, were H.I.V.-positive, they met with a number of potential buyers, none of whom, according to Eric, were equipped to handle the store’s intricate operations. In 1989, shortly before Tucker and Rohlfing succumbed to the virus, the newly married Eric and Laurie, with help from Eric’s brother, Marc, bought it themselves.

Photos by Daniel Terna

A summer job at the Pantry has grown into a coveted position. At 22, Emily Aracri, (below left) who has been working there for nine years, is finishing her final stint at the store before going off to law school. “Ever since I was young, I always knew that this was going to be my first job,” she says. “A lot of people in my family have worked here or on the ferries. It’s a very open community of people, who will do and say things that are not what other people might consider normal — and that’s OK. This is a whole different world.”

One wonders what these small-town teens make of the debauchery that surrounds them. Eric says that thanks to years of cross-bay lore, they know about the island’s eyebrow-raising antics, which can include any combination of drag queens, party drugs, frisky 20-somethings, friskier 50-somethings, vodka, tanning oil and jockstraps.

“Pulling money out of bathing suits is a big thing. Like, they’ll pull dollars out of their Speedos,” says Laurie. “But what are you gonna do? Just wash your hands afterward.” Kim Van Essendelft, the Pantry's current front-end manager, says, “I could write a book about what we’ve seen and heard here.”

Maybe it’s why even the seasonal employees keep coming back every year, and why, says Eric, the “cashiers, stock boys, produce boys, the dairy guy, bakery girls, meat guys, managers, the cook and delivery guy” are willing to show up and help out when such complications occur. (About that: If you miss the last ferry to the mainland at the end of the day, you’re stuck. And if you’re late for your shift because you’ve missed the ferry there, it’s one of three strikes before Laurie fires you.)

The biggest threat to the business is competition, although not from another shop. In fact, a rival grocery store did open in 2007, but it closed a few years later because of lack of interest in its upscale wares (and, according to Eric, poor planning). “That was nothing,” says Eric. “What’s affecting us much more are these Peapods.”

An online grocery service that delivers crates of supplies into the Pines, Peapod grew in popularity during the pandemic, and it’s making a dent in the Pantry’s sales. “There’s a younger generation coming in, and everything’s on their phone,” Laurie says. “They’re home late at night filling out grocery lists online because they don’t want anything to eat into their precious beach time. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing, but going to the grocery store is no longer a point of focus.” Eric is looking at a different type of screen, from a camera feed facing the harbor and showing stacks and stacks of crates awaiting pickup. “At one point in the mid-80s, the Pantry’s produce section was listed as the second-best cruising spot on the East Coast,” he says, smirking. “We try very hard to keep this a fun place for people,” Laurie adds. “We enjoy what we do and we enjoy the community. We want them to want to come.”

Artwork by Carlos Pisco 2020