Fire Island Art history- George Platt Lynes

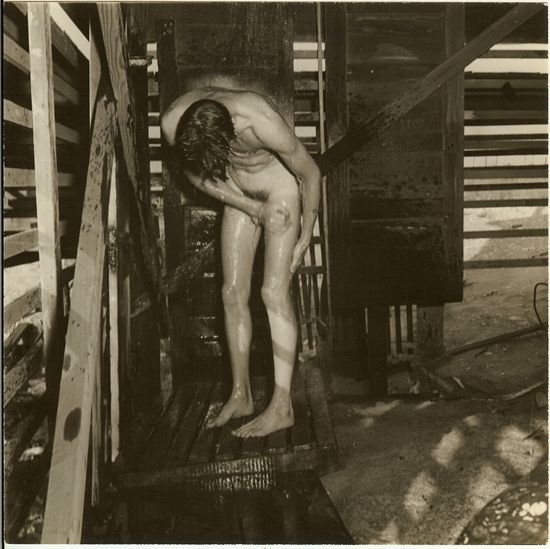

PaJaMa, George Platt Lynes and Jonathan Tichenor, Fire Island, c. 1941

George Platt Lynes was just one of a group of artist that found their way to Fire Island. Fire Island gave them a freedom to explore not only their art, but their lives. He with contemporaries like Paul Cadmus, Jared & Margaret French, Lincoln Kirstein, Bernard Perlin found Fire Island to be a refuge from a world that had no place for homosexuality. Here they could express their art and desires. Much like today...

From the late 1920s until his death in 1955, George Platt Lynes was one of the world’s most successful commercial and fine art photographers.

His work was included in one of the first exhibitions to showcase photography at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932, and he showed at the extremely popular Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. His photographs for Vogue and Bazaar, his shots of dancers at the School of American Ballet and his portraits of some of the most important creative figures of his era were lauded for their innovative use of lighting, props and posing.

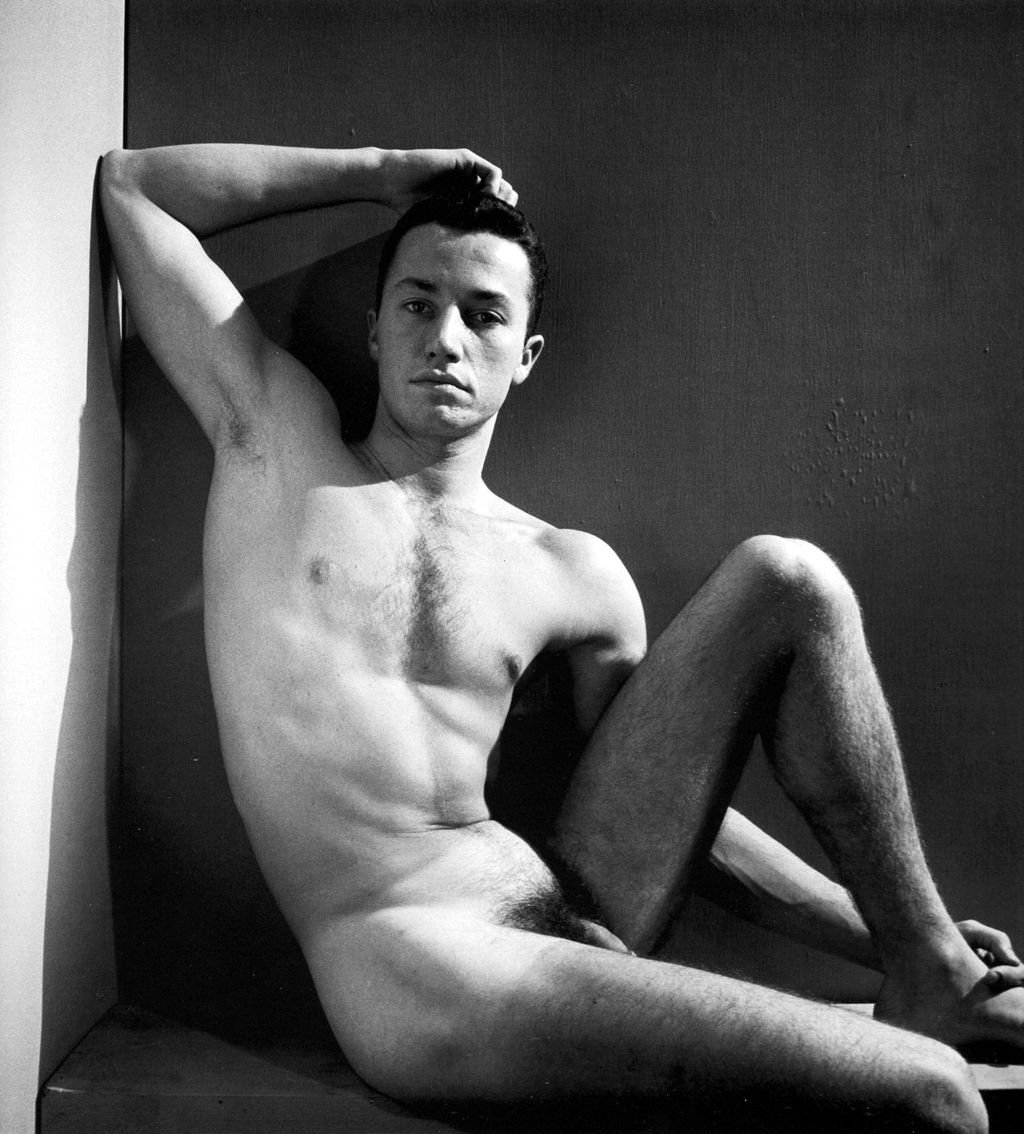

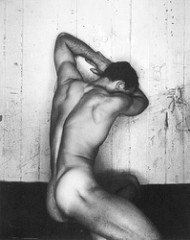

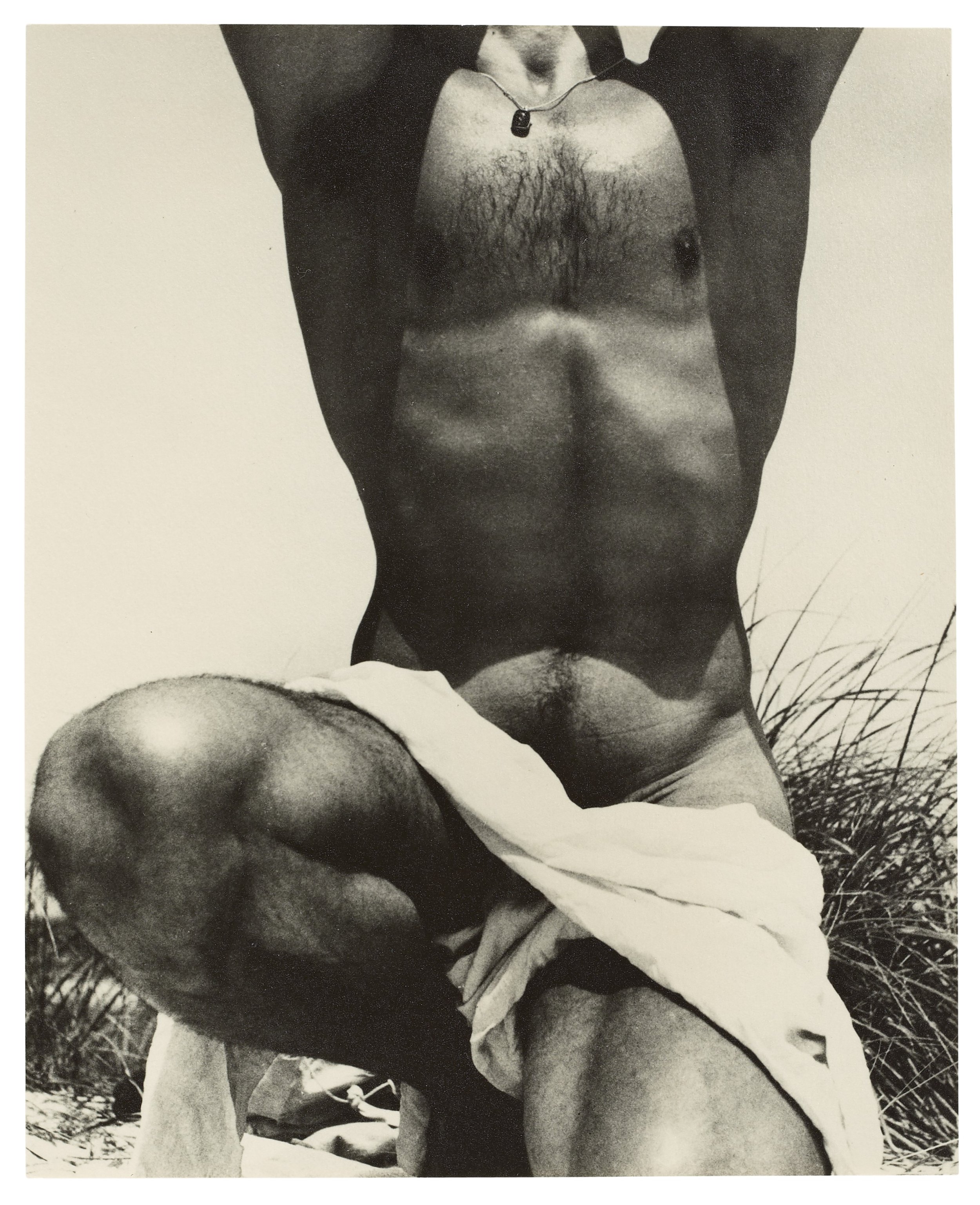

But in his view, his most important works were his nude photographs of men. Yet during Lynes’s life, few even knew of their existence.

Using inventive lighting, posing, and cropping techniques within his carefully staged studio settings, he was able to visually translate both the physical and psychological nuances of his subjects. His grayscale work is characterized by its sexual and homoerotic overtones, and is often shot in moody high-contrast. He photographed nude men, high-profile celebrities, and figures in the art world, lending his subjects a stylized sensuality through his extensive studio lighting and classical compositions.

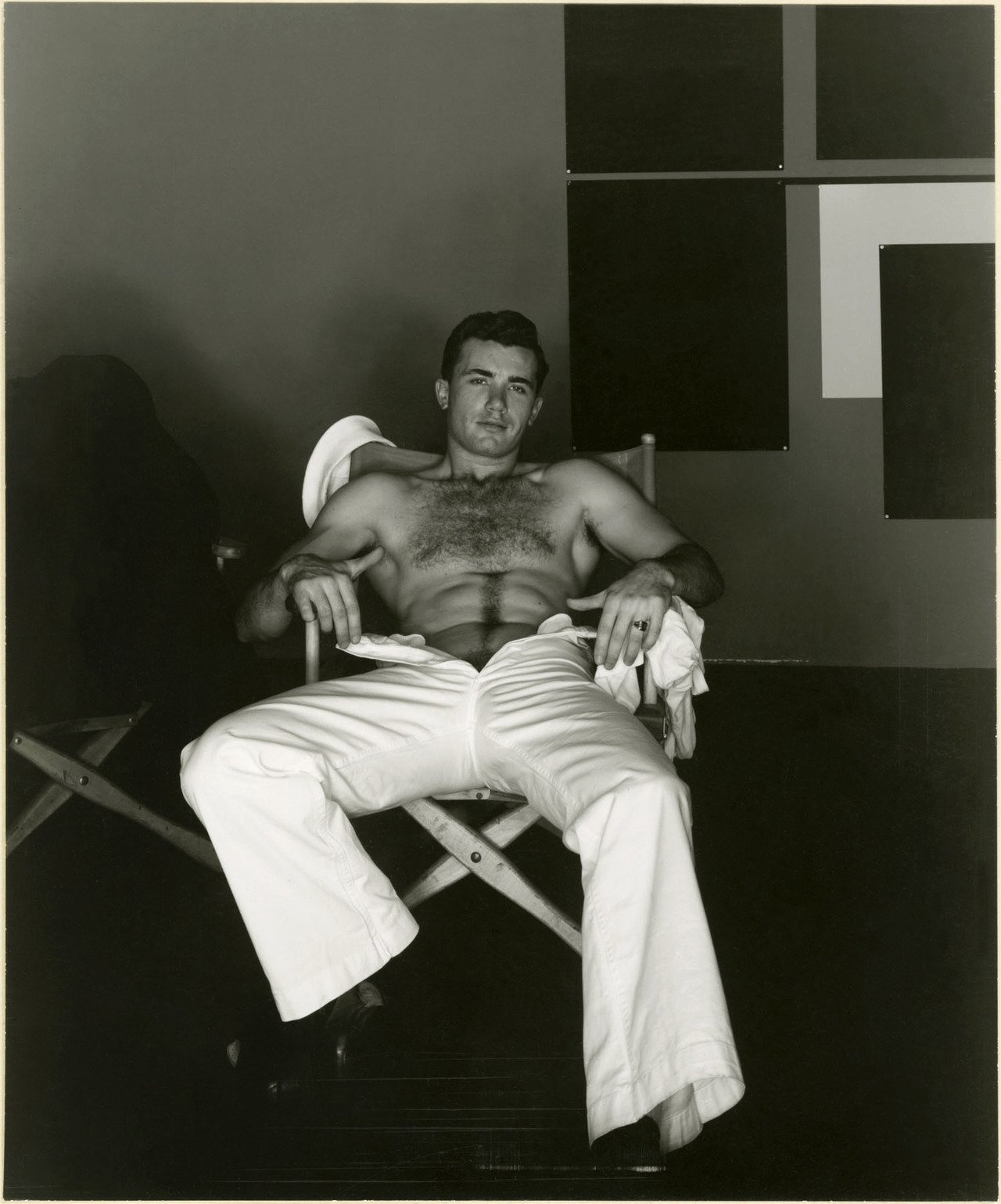

Left: Jonathan Tichenor, Fire Island, 1948; Right: Francisco Moncion, Fire Island, 1948

History…

Lynes attended the Berkshire School in Massachusetts and traveled to Paris for preparatory studies shortly after. In Paris, he met Réne Crevel, Man Ray, and Gertrude Stein, with whom he began a decade-long correspondence. Largely self-taught, Lynes eventually entered Yale University in 1926 and left after his first year to move to New York. Initially exploring writing and bookselling, Lynes soon found his aesthetic through the facility of the camera.

His first informal portraits were done in the late 1920s, but evolved to official society photography, contributing to significant museum shows, high-profile fashion magazines, and solo exhibitions. Indeed, his glamorous portraits of literary, film, and art world personalities are indicative of the types of personal relationships he had with them. His friendship with New York art dealer Julien Levy led to his first exhibition in 1932. Eventually, Lynes’ commercial success in portraiture and fashion photography enabled him to open his own New York studio in 1933. He later became the head of Vogue magazine’s West Coast studio in Los Angeles in 1946, where he moved following several years of emotional upheaval in his personal life. There, he photographed celebrities such as Katharine Hepburn, Rosalind Russel, Gloria Swanson, and Orson Welles.

Christopher Isherwood, Sir Cecil Beaton, Salvatore Dali, and Paul Cadmus.

Born in East Orange, NJ on April 15, 1907, Lynes began his career through self-taught photography, gradually arising to immense fame in his field. He worked for several high-profile New York-based clients such as Vogue magazine and Bergdorf Goodman, later turning his creative eye to the celebrities of Hollywood. He would come to disavow commercial work and return to personal photography projects later in life, going on to shoot his most celebrated and well-known male nudes.

At the prime of his career during the ’30’s and ’40’s, George Lynes, as he was called then, was exceedingly handsome, charming and persuasive. He was also at the epicenter of a circle of powerful homosexual men that exerted influence at New York’s artistic institutions. His early mentors were Monroe Wheeler, later the exhibition director at the Museum of Modern Art, and the writer Glenway Wescott, who provided Lynes with social cachet and business connections. An old school mate Lincoln Kirstein, later an arts impresario and a founder of the New York City Ballet, provided Lynes with commissions to photograph both George Balanchine’s dances as well as the company’s principal artists.

Lincoln Kirstein

Lynes supported himself with portrait photography for the socially prominent and fashion work for leading magazines, but those assignments didn’t hold his interest over time. In fact, before his death in 1955 at age 48, he destroyed most of his fashion work, the very photographs that had made him famous. His real passion was for the male nude, a pursuit he began as early as 1929. In view of prevailing laws and social climate, it was a daring undertaking. In fact, many times during his career, he was reluctant to send his nude photographs through the mail, fearful of legal reprisals.

Photographic shoots for the New York City Ballet gave Lynes ready access to good looking models. Sometimes models were paid for their services, but often lovers, friends, neighbors and even studio assistants were called upon to pose.

In the many ways Lynes worked with models, he was always in full creative control. He amassed a body of images that are as notable for their formal beauty as their quiet eroticism. His interest in glamour and design can be seen in his mastery of composition and dramatic studio lighting. In each picture, light is skillfully played against dark, as every element–prop, gesture, turn of a head or arm–rests in perfect, harmonious tableau.

T.S. Eliot

In an era when erotic photography of the male nude was taboo, Lynes was a true pioneer, composing stunningly beautiful pictures, revolutionary in their originality and sexually charged themes. The quantity, subject and quality of his work was prodigious for its time. With the privilege of hindsight, we can see the enormous influence of Lynes’ art on virtually all of the important photographers of the male nude that followed him.

Below Paul Cadmus, Jonathan Tichenor, and Jimmie Daniels.

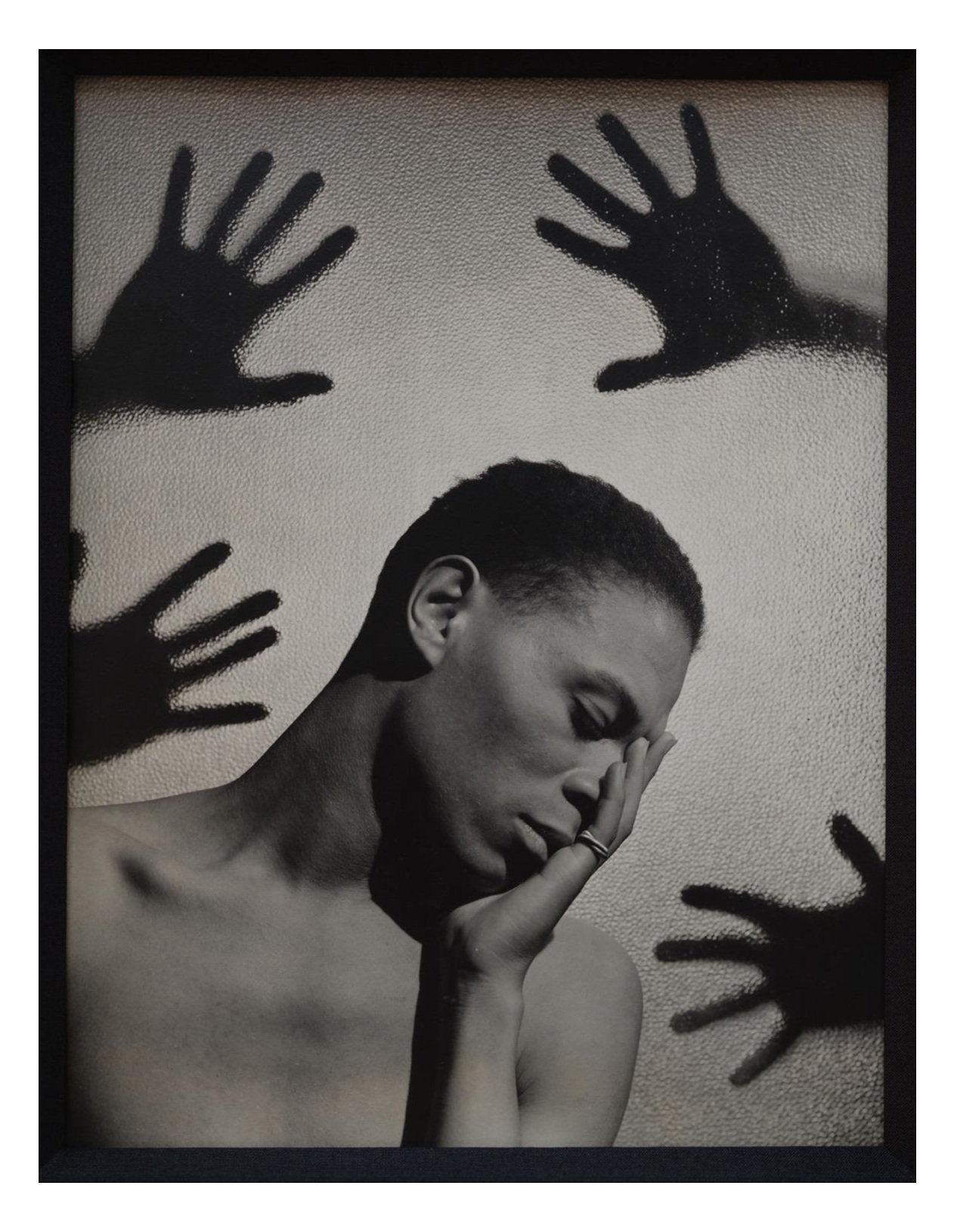

Jimmie Daniels, Singer at Le Ruban Bleu, 1933

Nudes and Mattress, 1941

In 1950 he had his final triumph shooting dancers from George Balanchine’s “Orpheus” wearing nothing but masks and props of Isamu Noguchi.

Lynes returned to New York and focused his photography practice on his private interests, male nudes, and documenting productions of the New York City Ballet. During this time, Lynes also became acquainted with Dr. Alfred Kinsey, an influential researcher on human sexuality who founded in 1947 the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, now known as the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction. A substantial body of Lynes’ nude and homoerotic photographic works were ultimately left to the Kinsey Institute after Lynes’ death in 1955.

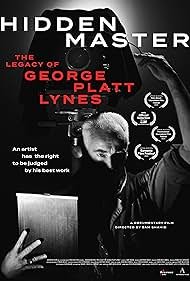

2023:

The release of the documentary Hidden Master: The legacy of George Platt Lynes